'We have to find ways to redefine generosity’

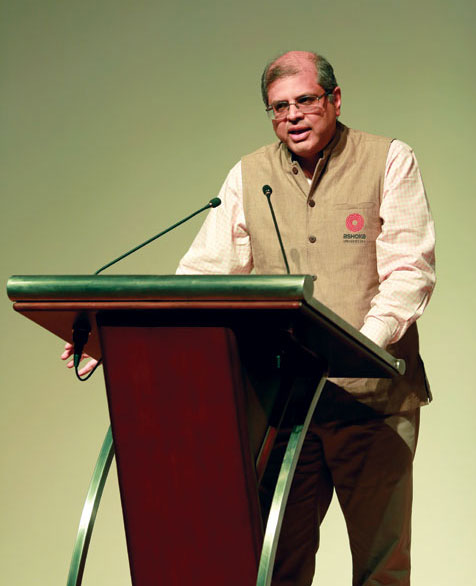

He is on the boards of global and Indian companies but it is not in the corporate space that Amit Chandra spends most of his time. His interests lie firmly in the social sector. Mr Chandra and his wife Archana — who runs the Jai Vakeel Foundation for those suffering from mental disabilities — aim to annually give away 75% of their net earnings for social causes.

In 2007, at the peak of his career as an investment banker, Mr Chandra gave up his position as a board member and managing director of DSP Merrill Lynch to devote more time for his philanthropic work. Currently he is the managing director of Bain Capital and is a part of the firm’s Asia senior leadership team.

Mr Chandra is closely associated with the Tata group, as a trustee on the Tata Trusts board and as non-executive director of Tata Sons. Among his many associations in the not-for-profit space, he is one of the founders of Ashoka University and a board member of GiveIndia, India’s leading philanthropic exchange.

In this interview with Christabelle Noronha, Mr Chandra talks about philanthropy, why India scores low on the charity scale, and the importance of collaboration in the social sector.

In a collaborative project you need to be very clear about who is doing what, you must have good reporting mechanisms, you need to have good communication on an ongoing basis..”

You have been called one of India’s most generous donors. What motivates you to give?

I think it is easy to be called one of India’s most generous donors because, unfortunately, as a society we have set a very low bar for ourselves in recent times. Very few industrialists and professionals say they want to use their wealth for society, and most find excuses to not do so.

I think the Tatas and a few others are notable exceptions who stand out. Even in the professional world there are a few people who have stepped aside to use their skills, time and money to help impact society. But there are not enough people doing that.

What do you think has brought about this change in terms of lowering the bar rather than raising it?

I don’t know; people have many excuses. Many blame the breakdown of institutions over the decades. I do find amazing generosity, though, among India’s poorest people and in people living deep in the hinterland. I feel what we must do as a nation is find ways to redefine generosity beyond the simple criterion of wealth. For instance, people who volunteer their time and skills are very generous and I have huge respect for them.

You have been vocal and open about your philanthropy and you believe that everyone should be. Why so?

This has been a difficult issue. To be frank, for a long time it was a big matter of debate between me and my wife, who is an equal partner in everything we do. Till we agreed, which took a while, we were very quiet about what we did and our philanthropy remained largely private and within our immediate circle.

There came a point when we decided that unless those of us who are engaged with philanthropic causes talked about it, we would not be able to build a broader philanthropy movement. I am very ambitious about my philanthropic goals, so we started talking more openly about it. We had come to the conclusion that we must start talking about our work in a thoughtful and measured way for it to have a multiplier effect, just like the way the work of others had inspired us to do more.

You have often spoken about the need for collaboration in social development, but that is not easy to work out. What are the challenges and how can they be overcome?

Both Archana and I are deep believers in collaborations, from a couple of perspectives. Collaborations are important for people like me who have somewhat limited resources, but for whom scale is a big aspiration. I needed to collaborate with others. Besides funds, forming a network brings knowledge and human capital.

In a collaborative project you need to be very clear about who is doing what, you must have good reporting mechanisms, you need to have good communication on an ongoing basis. And you need to have trust between the partners. One of the biggest impediments to success in a collaborative project is misalignment in objectives; if all partners don’t share the same vision, it can result in various degrees of conflict down the line.

With culture and trust, can such an environment be created?

I would reverse the order — it begins with trust. When trust gets broken, it becomes very difficult to rebuild it. Culture too is very, very important but we are still working on finessing this. That’s because there is no standard culture that can be replicated. Every organisation, whether it’s a corporation or an NGO, has its own culture, which comes from the leadership. We don’t impose our culture, but we try to emphasise openness, respect, communication and integrity.

It’s clear that partnerships with governments have the greatest potential to deliver large-scale impact. How can we ensure that these collaborations are successful?

For a long time, I personally stayed away from partnerships with governments because I had a notion that it would slow me down. Then I started working more closely with the government in projects related to water and that has changed my perspective.

You must understand that the government is not a monolithic entity. It is a set of people, just like any enterprise. I have met some exceptional officers in the government, people who are focused on time, on impact and are committed to development.

When it comes to partnerships with nonprofits, what are the advantages and impediments in the Indian context?

The biggest impediment is lack of capacity, which is why our strongest vertical is capacity building. It is a pity that little investment has taken place in capacity building for the not-for-profit sector. We have created a management, technical and scientific base in this country thanks to people like Jamsetji Tata, Dorabji Tata, Vikram Sarabhai and others.

How are we going to solve social sector problems if relevant organisations do not have the capacity to solve them?

Problems don’t get solved automatically; they get solved when you have exceptional leaders leading exceptional organisations. Many philanthropists and foundations in this country are myopic; they limit the funds NGOs spend on non-programme expenditure. They ask them to keep overheads low, almost as if overheads are a disease. But unless the core of the organisation is strong, its activities will not be scalable and it will be unable to make an impact.

“[The government] is a set of people, just like any enterprise. I have met some exceptional officers in the government, people who are focused on time, on impact and are committed to development.

What has been your personal experience in getting partnerships up and running in the social development sector?

Not all my partnerships have been successful, but I think failures teach you more than successes do, even though they bring a sense of disappointment. But it’s important, when failures happen, that you pick yourself up and move on.

Ashoka University, led personally by Ashish Dhawan, has been a wonderful partnership. There are now over a hundred of us who have got together in this movement and contributed more than ![]() 10 billion collectively to build what I think will be one of the top 500 institutions in the world over the next decade.

10 billion collectively to build what I think will be one of the top 500 institutions in the world over the next decade.

The journey is as enjoyable sometimes as the outcome. I have realised that life is not merely about the destination; it is also about the journey. I have also realised that, in India, unless you do work in the villages you have not really contributed meaningfully.

You have been described as a credible voice promoting philanthropy among entrepreneurs and professionals and as somebody who has helped define new ways to channel organised giving. How much of an effort does this involve?

I don’t make a conscious effort. While I get invited to speak at various forums, I try to share my experience as bluntly as possible. I know that the way in which my wife and I have organised our lives and organised our giving may be difficult for many people to follow.

Indians have been, generally speaking, tight-fisted with their money when it comes to philanthropy. Is this changing?

I am optimistic that change is happening, on two different dimensions. I have generally seen more openness to engage in this dialogue of giving among the wealthy; forums for philanthropy are becoming busier and attracting more people. I think the CSR bill has helped.

But I think there is greater hope on another front: India’s youth. You now have a number of young people who want to be active in shaping Indian society. Just look at how many of our brightest want to work in the social sector by choice. Therein lies hope.