The Lakhpati Kisan project is transforming the lives of over 100,000 tribal farming households in four Indian states — and it has the potential to deliver more

Kantibhai Makwana could barely make ends meet with what he earned by farming his field in Ratanpur village of Gujarat’s Sabarkantha district. Three years down the line, his income from agriculture has jumped from ![]() 25,000 per annum to about

25,000 per annum to about ![]() 175,000. The money has been meaty enough for him to do up his home — with a pipeline to boot, he says — buy a motorbike and start a flour-mill business.

175,000. The money has been meaty enough for him to do up his home — with a pipeline to boot, he says — buy a motorbike and start a flour-mill business.

Sushila Khanda, who lives in Gaduan village in the mineral-rich Keonjhar district of Odisha, was a subsistence farmer till three years back. A member of the Gond tribal community, she managed to pull in ![]() 73,000 last year, modest in comparison with Mr Makwana but good enough to complete the plastering work of her house, send her son to a better school and spend on clothes and trinkets.

73,000 last year, modest in comparison with Mr Makwana but good enough to complete the plastering work of her house, send her son to a better school and spend on clothes and trinkets.

Separated by some 1,800km and differences in language and culture, Mr Makwana and Ms Khanda have never met and are unlikely to. They are, nevertheless, part of a single extended family, one that has under its canopy more than 100,000 households in 800 underserved villages spread across the states of Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Gujarat and Odisha. This is the family that populates Mission 2020 — Lakhpati Kisan: Smart Villages, one of the most ambitious and challenging projects supported by the Tata Trusts.

The upside and after

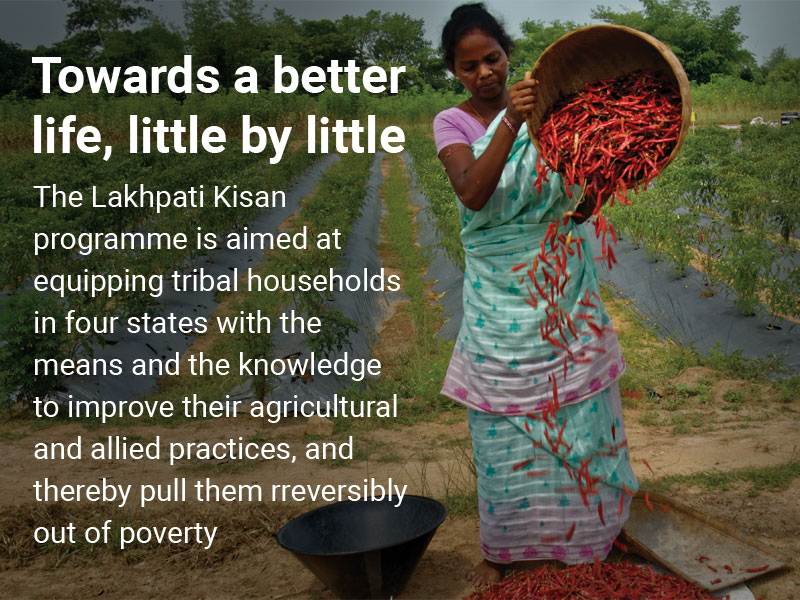

Lakhpati Kisan, loosely translated as ‘![]() 100,000 farmer’, is designed to lift those who have been incorporated into the programme irreversibly out of poverty. Operational since April 2015, it has a spectrum of schemes and principles to realise the objective, all of them aligned to agriculture-centred livelihoods. The households are mainly from tribal regions and the building blocks are women’s self-help groups (SHGs).

100,000 farmer’, is designed to lift those who have been incorporated into the programme irreversibly out of poverty. Operational since April 2015, it has a spectrum of schemes and principles to realise the objective, all of them aligned to agriculture-centred livelihoods. The households are mainly from tribal regions and the building blocks are women’s self-help groups (SHGs).

We were looking at raising the income of these farmers by three to four times. We had to think outside the box. We had to take ownership and risks and that’s what we have done.”

Ganesh Neelam, zonal manager, north and central India, Tata TrustsThe aggregation of SHGs into village organisations and, further on, into federations enables the project to gather strength in scale and nurture the women-led institutions spearheading their own development. The manner of the project’s execution pours attention on making the communities in its care resilient and cohesive, self-reliant and self-sustaining.

The goal is to get ![]() 120,000 into the hands of each participating household every year through farming and allied activities, bit by incremental bit. It’s a complicated task, made more difficult by the project’s stringent 2020 deadline for completion.

120,000 into the hands of each participating household every year through farming and allied activities, bit by incremental bit. It’s a complicated task, made more difficult by the project’s stringent 2020 deadline for completion.

Lakhpati Kisan is a welcome balm amidst the melancholy that envelops Indian agriculture, a pursuit rendered perilous for many by forces natural and induced. With its focus on tribal farmers and their fundamental problems, the programme aims to lift some of this gloom and, it is hoped, provide a template that can be employed by governments and their agencies to similar effect on a wider canvas.

Lakhpati Kisan supplements and often times supplants the ways of traditional farming. That means adding on to conventional crops such as maize, wheat and paddy with high-value vegetables. It means improving irrigation access — drip irrigation is a crucial feature of the project — and water usage efficiency. Also on the menu are year-round farming, developing linkages to markets, aggregation of produce to fetch the right price and backing tribal entrepreneurs.

More than farming

Alongside high-value agriculture, participating households have been encouraged to take up at least one allied livelihood activity — such as animal husbandry, apiculture, lac cultivation, fisheries and horticulture — to hedge risks as well as accelerate income growth. The focus has been on technology and innovations, among them polyhouse nurseries, trellis farming and solar-based lifting devices.

Initiatives for all-round improvements in the quality of life of tribal communities — with projects in education, water and sanitation, nutrition, digital literacy, sports and life-skills development — have been integrated in community clusters.

Lakhpati Kisan emerged following a study done in 2013-14 to understand the dynamics of farming by small landholders in India, the bottlenecks they have to deal with and their successes. Vital in this context was the need to spark the community’s aspirations and enterprise, to bring together its talents and efforts to ensure the permanence of change.

Collectives for Integrated Livelihood Initiatives, an associate organisation of the Tata Trusts with more than a decade of experience, became the natural vehicle to seed the project and drive it forward. Nonprofits, many of them already working with the Trusts, were brought in to help with implementation. Once off the ground, the programme also connected with government bodies and schemes to intensify the impact of its various endeavours.

What Lakhpati Kisan is trying to accomplish is distinctive, and that poses challenges by the dozen. “We realised we couldn’t do the regular stuff and expect to succeed,” says Ganesh Neelam, who heads the initiative. “We were looking at raising the income of these farmers by three to four times. We had to think outside the box on all aspects, including technology, irrigation, getting other stakeholders on board, and building capacities and institutions. We had to take ownership and risks and that’s what we have done.”

The goal:

To enable 101,000 tribal households to earn at least ![]() 120,000 a year

120,000 a year

Geographic spread:

800 villages in the states of Odisha, Jharkhand, Gujarat and Maharashtra

Project period:

From 2015 to 2020, by when the initiative is expected to be sustainable

The catalysts:

Tribal women, trained and supported,form the core of the programme

Institutional setup:

5,300+ self-help groups, 340 village organisations, 19 federations and farmer-producer organisations

The methods:

High-value crops, year-round farming, improved irrigation, access to markets, aggregation of produce, animal husbandry, etc

X factor:

Use of top-end technology for farming, water and sanitation, energy, education and health, and digital literacy

Miles to go

With three years of the programmes completed, not everything has gone according to plans and expectations. “We have covered in excess of 100,000 households in Lakhpati Kisan and the idea was to get at least 50% of them to an income level of at least ![]() 120,000 a year by now,” says Mr Neelam. “Our current achievement stands at 20%, so we are behind the target. It has taken longer than we expected to build capacities in the community and to get people to try out new things.”

120,000 a year by now,” says Mr Neelam. “Our current achievement stands at 20%, so we are behind the target. It has taken longer than we expected to build capacities in the community and to get people to try out new things.”

Mr Neelam is confident that progress from here on will be faster. “This is our fourth year and I’m sure that by the end of it we will have about 70% of our farming families with an income of ![]() 100,000 and more. The community institutions, the technology and the training are broadly in place today and we are working on the market linkages part. When we kicked off we had certain hypotheses; those have evolved and we have adapted.”

100,000 and more. The community institutions, the technology and the training are broadly in place today and we are working on the market linkages part. When we kicked off we had certain hypotheses; those have evolved and we have adapted.”

Mindset change

Hidden from view is the psychology of villagers making the leap from traditional agriculture to high-value crops. The majority of these folks were not full-time farmers to begin with and it has taken a while to bring them up to speed. “It requires substantial energy to understand the mindset of the villagers,” explains Mr Neelam. “We spend six to eight months interacting with the community before we get started and there are a lot of challenges in convincing them about the multiple facets of the initiative.”

There have been variations in outcomes in the four states covered by Lakhpati Kisan. The positive here is the cross-pollination of ideas and the sharing of knowledge from every success and failure. “Gujarat stands out because the institutions there are strong; the people there had an early start and they are proactive,” says Mr Neelam. “In Odisha and Jharkhand the adoption of new technologies has been fast. In Maharashtra, village institutions have come to the fore. It’s basically about learning from one another and going up the ladder.”

Having the state governments on its side is critical for the programme and this, too, is a demanding job. “You have to stay engaged,” says Mr Neelam. “What we have learned is that we need to be close to the official machinery at the district level; they are the ones calling the shots.”

The reality on the ground is what occupies the attention of Santanu Dutta, the man in charge of the project in Odisha. “In the tribal regions we work in, it is mostly subsistence agriculture, mono crop and rain-fed,” he says. “The villagers are not habituated to the commercial growing of crops, which requires a superior degree of skill and experience. We had to create the momentum and the mahol [atmosphere] to attract them.”

There were other issues as well in Odisha: shortage of labour, inadequate access to irrigation, lack of market linkages and communities that found it difficult to get mobilised. What did work was drip irrigation and getting connected to the market. “Drip irrigation is not about saving water as much as it is about saving on labour,” says Mr Dutta. “And it’s not about isolated irrigation structures; you have to saturate the villages with irrigation access.”

Community care

Virendra Vaghani, Mr Dutta’s counterpart in Gujarat, says the Tata Trusts confronted a different set of challenges in the state. “Initially it was about convincing our field partners on the feasibility of the initiative. Then came setting up the SHGs, the primary institutions in Lakhpati Kisan. We were a bit late on this but we have caught up. We got the community to take charge. Once that happens you can trigger aspirations and it becomes easier.”

Change agents from within the community are important cogs in the programme and Mr Vaghani and his team have come to depend heavily on them. “We selected the progressive ones and started with them. They were open to new ways of doing things and we showed them how. Other farmers saw the result, believed in it and the village as a whole adopted the approach.”

Mr Vaghani emphasises the need to give the community more space and responsibility. “They may fail but they will learn from it. Having said that, I must add that I’ve never seen the community contributing as much in any programme. I’m very optimistic that we will achieve our results.”

Lakhpati Kisan is still in the first stage of implementation, which is about enhancing livelihoods and getting households to the ![]() 120,000 mark and beyond. The second phase, which has been initiated in select clusters, will see greater stress being put on quality of life indices. In the thinking of the Tata Trusts, what lies after that is a surety.

120,000 mark and beyond. The second phase, which has been initiated in select clusters, will see greater stress being put on quality of life indices. In the thinking of the Tata Trusts, what lies after that is a surety.

Sustainability equation

“Our involvement will be reduced substantially and the community will take the lead,” says Mr Neelam. “What we are also saying is we have a fine opportunity here to scale-up the initiative, through the institutions that have been put in place and by getting the government convinced that this concept can be taken far and wide.”

The Tata Trusts have committed significant resources to the Lakhpati Kisan programme, spread over its five-year duration. About as much will come in from other donors and government agencies. More heartening still is the monetary contribution the villagers are making to their own uplift. Where 10% or less is the norm, these villagers are putting in 20-30% of the money required.

“I don’t know what plans God has for me but I believe things will get better,” says Mr Makwana, who, unlike scores of farmers across India, does not think agriculture will be anathema to those following in his stead. “I have a grandson now and, with the progress we have achieved, he will do four times as well as me.”

The upbeat nature of Mr Makwana and his mates is not an aberration. After all, it is difficult for those who can afford to take the necessities of everyday life for granted to understand the difference a swell in money earned makes to those surviving on the margins. Not so for Shardaben Makwana, once a sharecropper with an income of ![]() 40,000 a year, now a rejuvenated farmer who made

40,000 a year, now a rejuvenated farmer who made ![]() 150,000 in 2017. Asked what the future holds for her, she says, “Next, I’m headed for the moon.”

150,000 in 2017. Asked what the future holds for her, she says, “Next, I’m headed for the moon.”

‘There was so much to discover’

Sumitraben Patel, a self-assured 60-year-old from the Bhil tribal community, is an example of how Lakhpati Kisan is enabling farmers of modest means to fashion a better life for themselves. A resident of Dhabada village in Gujarat’s Dahod district, Ms Patel has hauled herself and her family up from a hardscrabble existence to find a fair measure of security, a voice in her community and her place in the world. This is her story:

Traditional, low-scale farming was what we were doing and we grew maize, wheat and pulses. The work was tough and the money we made barely enough to get by. There were plenty of days when we struggled to put decent food on the table; dal-roti was the staple. Then came the Lakhpati Kisan project and it transformed everything.

The programme opened our eyes. The training and learning, the exposure to better farming practices, the coming together of our women through self-help groups [SHGs], the growing of cash crops, the concept of year-round cultivation, the aggregated marketing and selling of produce — all of these were part of the programme. There was so much to discover and understand.

We had an irrigation scheme in our village but the Lakhpati initiative was the real accelerator. I was making ![]() 50,000-60,000 a year before the programme was introduced in 2015. Now, three years later, my family’s income has risen to

50,000-60,000 a year before the programme was introduced in 2015. Now, three years later, my family’s income has risen to ![]() 300,000 a year. We grow vegetables, we produce honey and we have a small business providing decorations, catering and music bands for weddings. None of this would have been possible without the programme.

300,000 a year. We grow vegetables, we produce honey and we have a small business providing decorations, catering and music bands for weddings. None of this would have been possible without the programme.

The money coming in has been a huge help for my family. We have been able to refurbish our house, invest in digging borewells and also fund the education of my grandson, who’s studying to be a homeopathic doctor. As for me, I’ve gained so much confidence from the project. My grandkids may well find employment elsewhere, but there is no question of me giving up on agriculture. Besides the money, we get to eat fresh and wholesome food. No pesticides.

I was the one who took the lead. My husband is the kind who does not like taking advice from outsiders; I wanted to listen to everybody and learn from them. I mobilised other women from my village to form one of the earliest SHGs in the project.

I used to work for daily wages before joining the programme. No matter how sincere my labour, there would always be complaints. I was convinced that if I put in the same effort on my land, and with the knowledge I had gained, at least there would be nobody complaining. This is my field, my produce, my earnings, my business. That makes me feel good.

I can’t read and write and that’s a disadvantage, but my position in the family is strong. The final word is mine. That definitely is due to what I have achieved. Thanks to the exposure I got, I learned about the world and how it functioned, about leadership and organising people. There was a time when I wasn’t comfortable sitting on a chair. That’s long gone.

I’m certain we can sustain this success even after the project winds up here. We have moved from growing crops to marketing them. We have become entrepreneurs. We have created vibrant village communities that can speak — and do good — for themselves.