Class comfort

School dropouts are back in the education system thanks to an initiative targeting rural communities in Assam

His father’s untimely death in 2018 came as a shock to Sengprang Momin, then just nine. Struggling with grief and emotional turmoil, the lad from Derek Jongnapara village in Assam’s Goalpara district cut himself off from his friends. The bereavement plunged the family into a financial crisis, Sengprang’s private-sector school refused to take him back because his mother couldn’t afford the fees any longer, and he missed classes for an entire year.

The opportunity to get back on track with his learning arrived for Sengprang in late 2019, when he came on the radar of the Tata Trusts’ Assam state initiative (ASI) education programme, an effort to help out-of-school children like him. After speaking to his family members, the ASI team convinced Sengprang to participate in a 15-day motivational camp.

Mingling and engaging with his peers at the camp made a world of difference for Sengprang, who now studies in class IX at the Derek Higher Secondary School, a government-run institution where education is free. “ASI has given us hope,” says Sengprang’s mother, Pretisa Momin. “Without this project my son may never have got another chance to get back to his studies.” Ms Momin wants Sengprang to become an army officer and, the way things are going, the prospect is far from distant.

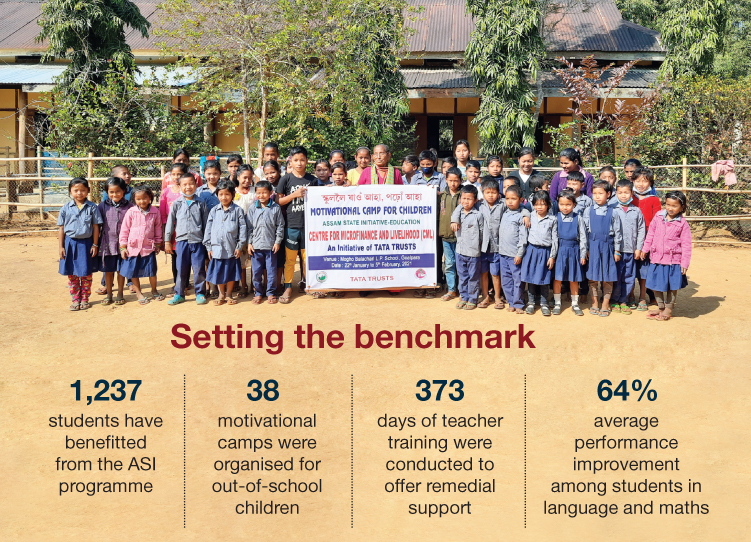

Labour migration and abject poverty force countless children across Assam to drop out of school every year. The problem is more pronounced in rural areas, and it’s here that ASI has made its mark. The programme has thus far enabled 1,237 children from four districts — Goalpara, Bongaigaon, Baksa and Nalbari — to resume formal schooling.

Says Benny George, area manager for education (Northeast) with the Tata Trusts: “All four of these districts face major challenges with regard to student dropout rates and learning outcomes. It made sense for the Trusts to launch an educational intervention of this kind in these districts.”

Schooling springboard

For his circumstances and the background he comes from, dropping out of school after class VI was seemingly inevitable for 10-year-old Sulman Ali (above), and a natural course of events as far as his hard-pressed family was concerned.

Sulman’s father is a migrant factory worker in Kerala and his grandparents, who live in Chapatal —an underdeveloped pocket in Assam’s Baksa district — were too poor to send him to school. Sulman’s tender age was no bar to him joining the family vocation of cutting betel nuts.

That’s how it would have stayed if not for the Assam state initiative (ASI) education programme. The ASI team convinced his grandparents to send Sulman to a 15-day motivational camp at Kalakuchi Lower Primary School. The experience encouraged him to get back into the formal schooling system and, with the ASI team’s help, he enrolled at the Chapatal Middle English School.

Returning to school has transformed Sulman in more ways than one, in his behaviour, his sense of discipline, his confidence and his interests. Sulman’s overall development has improved on every education parameter and he has made many friends. His family members couldn’t be happier as they see the shy young boy coming into his own, and his prospects of improving his lot in life have never been brighter.

It’s a lesson well learned by Sulman, his parents and grandparents and the community he belongs to.

Implemented by the Centre for Microfinance and Livelihood (CML), an associate organisation of the Trusts, the big goal of the programme was reducing school dropout rates by at least a quarter in the selected districts. Also on its agenda were retaining three-fourths of the targeted children in school through remedial support and pulling dropouts and never-enrolled children into government schools, Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalayas and Residential Special Training Centres.

Pillars in the process

Village communities and teachers were vital pillars in the process. The ASI team created community platforms and worked closely with school management committees and mothers’ groups to push the endeavour forward. Additionally, there was a capacity-building component for schoolteachers (through training workshops).

ASI worked exclusively with government schools, where the remedial need is highest. Fanning out across the project area, the programme team located dropouts by visiting homes and talking to family and community members. Motivational camps were conducted to convince children to stick with, or get back to, formal schooling.

Remedial classes for re-enrolled and poorly performing children were held on alternate days of the week. The young ones got extra help from 45 educational facilitators, who were tasked with monitoring 90 schools in the project area.

The role of these facilitators in improving the literacy and numeracy skills of students was crucial to the programme’s success. Kandarpa Kalita, area manager for education at CML says that in many cases the facilitators had to start by teaching the absolute basics. These were children who could not even recite the alphabet (neither in their native language nor in English). They needed plenty of support to catch up.

The requirement for such support was clearcut. “We had class V students who had to be taught the lower kindergarten-level curriculum,” says Mr Kalita. “Although these students have still not caught up with the rest of their class at the end of three years, they now certainly have the capacity to do so.”

The remedial process was not without conflicts, as schoolteachers were sometimes reluctant to send a child away from class every alternate day. This was where the teacher training workshops had an impact. Apart from giving teachers the tools to make learning fun for the kids, the workshops also drove home the need for foundational literacy and numeracy. The tutors were made to understand that teaching a child the nuances of grammar or advanced maths is meaningless if he or she is unable to recognise alphabets or numerals.

Literacy and numeracy

“Some of the children could add and subtract mentally or orally, but they could not do sums on paper because they didn’t have an adequate grasp of numbers,” says Mr Kalita, who adds that focusing on literacy and numeracy was essential to ensure that the children kept returning to class. “The teacher training programmes, meanwhile, helped teachers understand the value of building a bond with kids.”

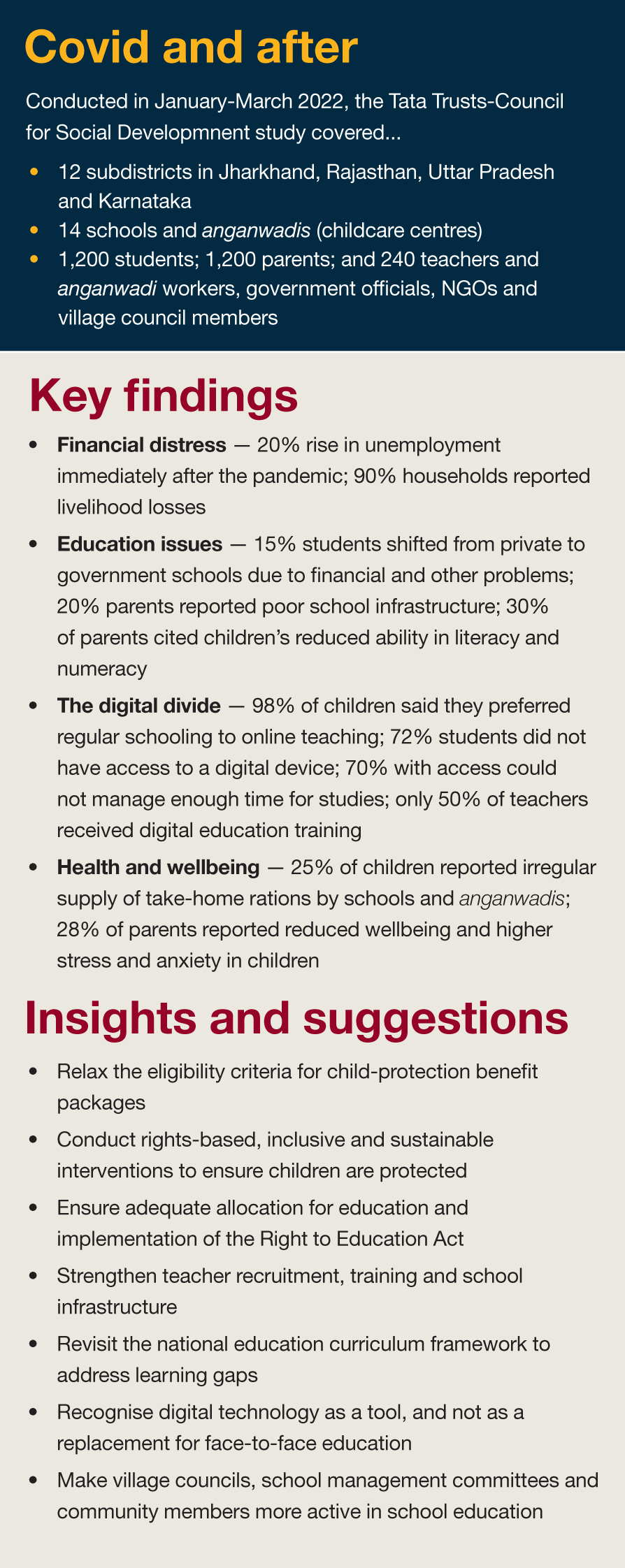

Launched in September 2019, the ASI programme was stymied by the Covid pandemic before it could get into full gear. The country-wide lockdown in March 2020 led to schools being shut until February 2022. This dealt a major blow to education especially, as many families were too poor to afford smartphones for their children’s online classes.

Education facilitators working with the programme overcame this problem by visiting student homes to conduct remedial learning sessions. The rapport they had built with the children in the preceding months came in handy. Initially diffident, the parents of these students became deeply involved in their children’s studies (despite many of them never having gone to school themselves). “It was touching to see the pride on the faces of parents when their children began to read simple stories from their textbooks,” says Mr Kalita.

Through determination and sustained effort, the ASI team succeeded in meeting, and in some cases exceeding, its objectives. An example of this is the improvement in learning outcomes of students attending the remedial classes. The team had set itself a performance improvement target of 50% for language and maths. The actual improvement has been 64% on average.

Leela Das, headmistress of the Kalakuchi Lower Primary School, is all praise for the ASI effort. “The remedial support through education facilitators is an excellent idea, and has worked very well for our children,” she says.

Bringing the children back to school has been a fulfilling experience for the educational facilitators involved. Manoj Talukdar, a facilitator from Tamulpur village in Baksa district, is thrilled to get the opportunity to give back to his community. “The kids are benefitting from my teaching and every day I learn something new from them, too,” he says.

While the ASI programme ended in March 2023, an expanded one is set to be launched in the near future. “We will cover more districts and schools in Assam. Our aim is to reintegrate 2,500 more out-of-school children into the education system,” says Mr George.