The lady lives on

Established by Dorab Tata in memory of his wife, Meherbai, the Lady Tata Memorial Trust continues to support leukaemia research

Dr Mammen Chandy is a former director of the Tata Medical Center, Kolkata

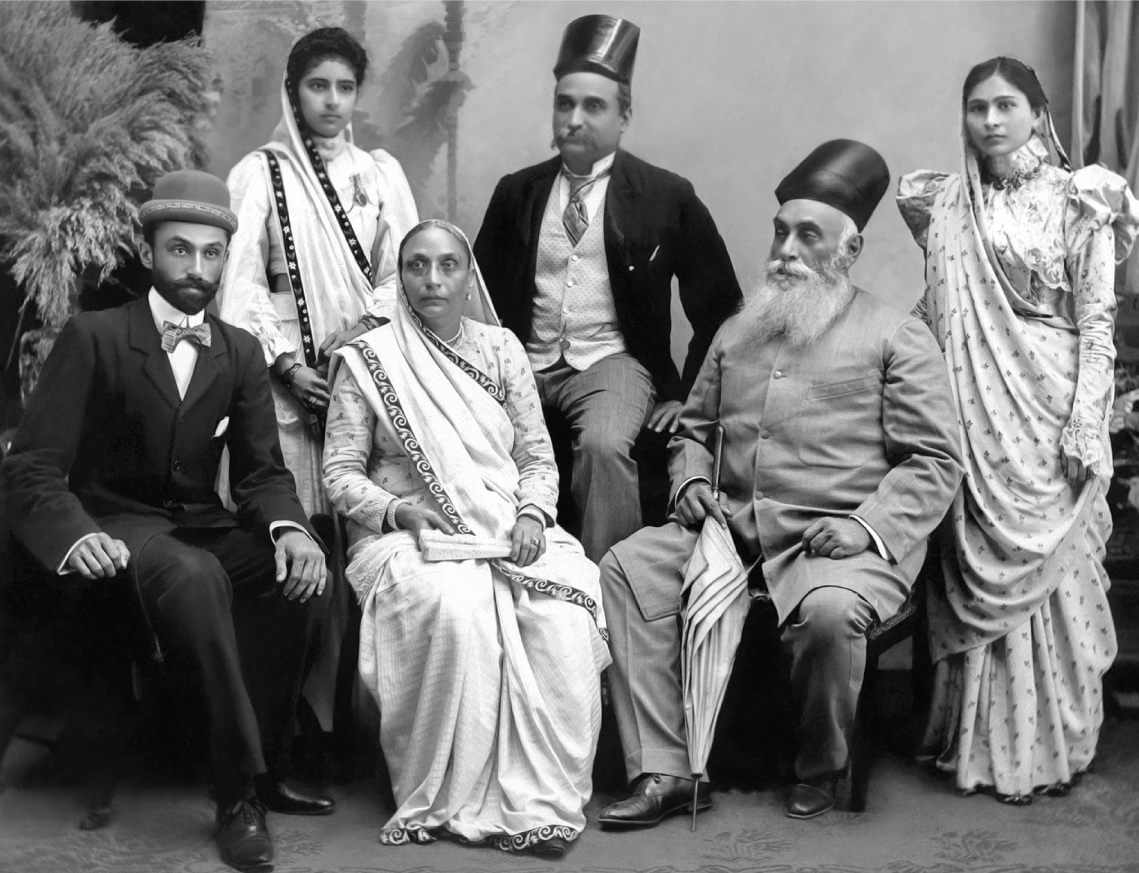

Lady Meherbai Dorab Tata was a woman of personality and substance. Possessed of a rare intellect, she was a talented pianist and connoisseur of English literature, India’s first woman Olympic athlete, the first Indian woman to fly in an airplane, and — perhaps most important — a champion for women’s rights. The much-loved wife of Dorab Tata and daughter-in-law of Jamsetji Tata, the founder of the Tata group, Lady Meherbai Tata continues to live in the collective memory, and appropriately so.

The Lady Tata Memorial Trust (LTMT) was established by Dorab Tata in April 1932 in memory of Lady Meherbai, who succumbed to chronic myeloid leukaemia — an eminently treatable disease that today can be cured with an oral pill — in June 1931 in a nursing home in Wales at the relatively young age of 51.

LTMT has since its inception funded scientific research in blood-related diseases, with a focus on leukaemia. Dorab Tata also established another trust in his beloved wife’s name, the Lady Meherbai D Tata Education Trust, which enables Indian women graduates to pursue higher studies abroad.

Lady Meherbai was born in Bombay on October 10, 1879. She was educated at Bishop Cotton School in Bangalore when her family moved there following her father Hormusji J Bhabha’s appointment as principal of Maharaja’s College in Mysore.

An accomplished pianist

After passing her matriculation exams at the age of 16 and attending college for science classes, Lady Meherbai continued her education in her father’s extensive library. A missionary lady was enlisted to supervise her reading in English literature and impart music lessons. The young Mehri soon became an accomplished pianist.

On February 14, 1898, Mehri married Dorab Tata, Jamsetji Tata’s elder son and inheritor of his father’s responsibilities as head of the Tata group. Dorab gifted his new bride the 245-carat ‘Jubilee diamond’, named after Queen Victoria’s centenary anniversary. There’s a story here that’s more than worth telling.

Twice as large as the Koh-i-Noor, that complicated icon of colonial plunder, the Jubilee diamond was discovered in a South African mine in 1895 and acquired by a consortium of London diamond merchants. The consortium displayed the diamond at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, which is where Dorab Tata and Lady Meherbai purchased it for £100,000. Every time the Tatas removed the Jubilee diamond from their safe deposit vault in London for Lady Meherbai to wear, they were reportedly ‘fined’ £200 by the insurance company.

Lustrous as the donning of it may have been, the Jubilee diamond would serve a greater purpose for the Tatas: it was part of the jewellery pledged by Dorab Tata to the Imperial Bank when the Tata Iron and Steel Company — today’s Tata Steel — was undergoing a crisis in 1924. The diamond was eventually sold following Lady Meherbai’s demise, along with the rest of her jewellery, to set up the trusts in her name.

Women in similar circumstances may have been content to bask in the triumphs of her family and her position, but Lady Meherbai was made of different stuff. She put to good use the liberal education she had received, advocating the case of women in India and becoming one of the founders of the Bombay Presidency Women’s Council as well as the National Council of Women.

Lady Meherbai was a crusader for the advancement of women’s education, and for abolishing the purdah system and the practice of untouchability. Dorab Tata wholeheartedly supported his wife’s interests, encouraging her to take charge of a local school in Bombay and transform it into a model institution.

Female education

Together, they brought in an expert from England to conduct a survey on the state of female education in India. This extensive survey took over a year and the resulting book, which documented the findings, became for many years the handbook provided by the Board of Education in Whitehall to all women inspectors before they made their way to India to promote higher education for girls.

Coming to LTMT and the yeoman service it renders, the Trust spends four-fifths of its income on international research. An ‘international scientific advisory committee’ based in London invites applications for awards of support grants for leukaemia research worldwide. These awards cover studies of leukemogenicity, and the epidemiology, pathogenesis, immunology and genetic basis of leukaemia and related disorders (including myeloma and lymphoma).

These awards are open to qualified investigators of any nationality. Priority is given to those intending to move to other centres to establish scientific collaboration between laboratories and/or progress towards scientific independence. The awards have been granted to researchers from all over the world, an example being David Hernandez Cruiz from Mexico, who received his DPhil from the University of Oxford, thanks in part to LTMT. The award enabled Mr Cruiz to pursue research on mutations in leukaemia, especially in children with Down’s syndrome.

Another to benefit from LTMT’s support is Remi Safi, currently a postdoctoral research fellow at the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain. This is what she had to say about the LTMT grant, which she received in the 2022-23 award cycle: “I started a ‘high-risk’ project aiming to decipher — for the first time — the role of lipid droplets in acute myeloid leukaemia.

“While the project has yielded promising data, more time is needed to finalise our findings and publish impactful results. In the meantime, I have published two peer-reviewed papers in the lipid droplets field… The fellowship secured my stay in top-notch laboratories and has equipped me with the skills to address significant research questions, provided training in scientific grant writing, and enabled me to establish my own research niche.

“Securing the Lady Tata Memorial Trust grant provided me with an exceptional opportunity to receive the prestigious Marie Sklodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship. I am currently in the second year of this fellowship, which has been an enriching experience.”

LTMT offers one-fifth of its income to scholars doing scientific investigations in Indian universities and institutes into diseases of the blood — with special references to leukaemia — and for scientific research in the alleviation of human suffering from the disease. The awards offered are for post-doctoral fellowships (two-year term) and junior scholarships (five-year term leading up to the senior scholarship and doctoral studies).

Numerous institutions, for research and for medical treatment, have received grants from LTMT and this has helped enormously in the further investigation of leukaemia and in allied research.

The Trust’s budget estimate for 2024-25 is ₹114.7 million (11.47 crore). This may be smaller than the contributions of the bigger Tata Trusts to social causes, but there is no doubt about its value. LTMT has encouraged young researchers all over the world to take up the challenge of finding out the reasons why blood cancer develops, and to develop therapies that can combat it. Lady Meherbai Tata would surely be a supporter of such backing.