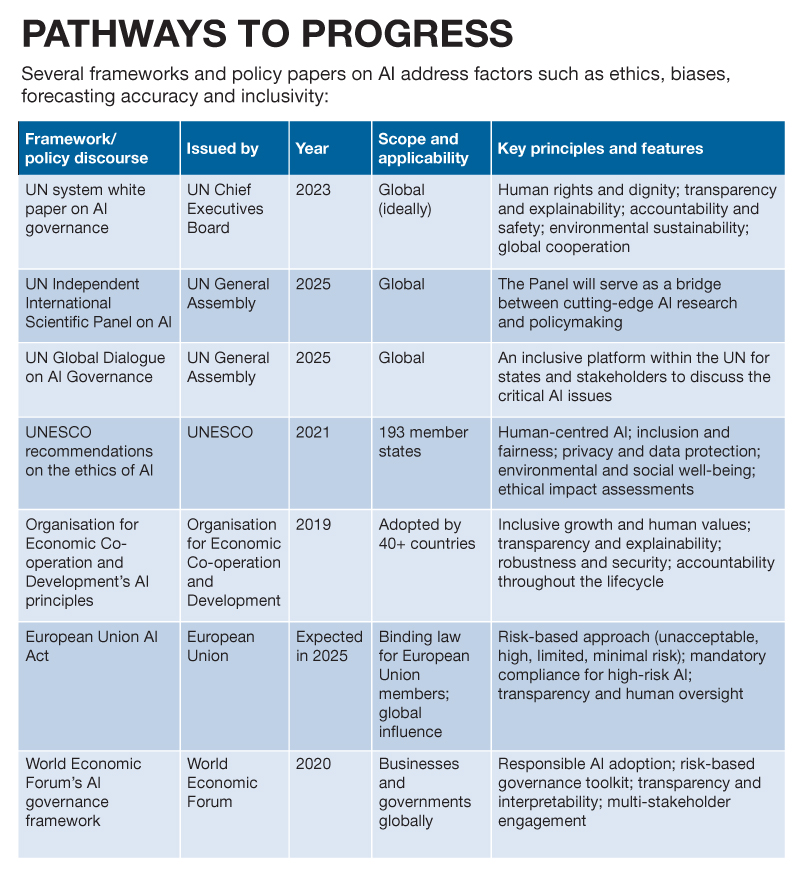

Measured matrix

A robust ‘monitoring, evaluation and learning’ framework is critical for evidence-driven social development programmes to realise their full potential

Over the past few decades, there has been a significant increase1 in the number of NGOs in the global development sector, with more than 490,000 in India alone. Alongside the growth of these NGOs is a transformation in their size, scope

and mandate.

No longer confined to small-scale service delivery, NGOs today are critical development actors with complex roles and responsibilities, including mobilising resources, designing and implementing programmes, and holding governments responsible.

However, a persistent constraint remains for NGOs — chronic underfunding. Research describes this as systemic deprivation or a ‘starvation cycle’, driven by donor funding models that prioritise programmatic spending while limiting investment in essential internal capacity development.

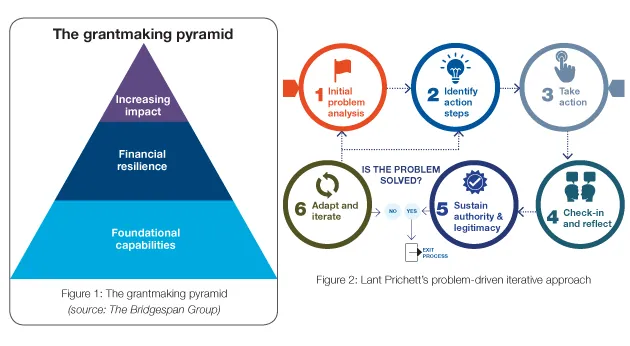

A study by the Bridgespan Group2 highlights a worrisome paradox: NGOs are expected to deliver impact at scale without the resources to enhance the staffing capabilities required to do so (figure 1).

The study underscores the importance of capacity strengthening for strategic planning; monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL); and talent and leadership development. These are key enablers for achieving programmatic outputs and important drivers of impact. Philanthropist Amit Chandra3 puts it succinctly: “Capacity building has a return on investment that is a multiple of programme investments, and is often self-sustaining.”

India’s philanthropic ecosystem is slowly addressing this challenge. Dasra’s India Philanthropy Report 2023 notes that 90% of ‘Inter-gen and now-gen’ philanthropists are open to catalytic approaches such as long-term funding, collaboration and knowledge sharing. Its 2025 report further shows that Indian diaspora families are increasingly providing flexible funding to grassroots NGOs.

Sohini Mookherjee is the project director, special initiatives, at J-PAL South Asia.

Although capacity-building opportunities funded by donors span many organisational priorities that are critical for the success of NGOs, it is MEL that plays a vital role here. MEL enables NGOs to generate evidence, learn from programme implementation, course correct in real time, reallocate limited resources, and scale programmes that work, ultimately shaping the effectiveness of donor investments.

Capability building

Donors must invest in MEL, rather than leave it to be self-funded by grantees. Translating this intent into practice requires Indian philanthropy to finance long-term MEL capability building as a key feature of programmatic funding, particularly through flexible and unrestricted support.

Drawing on nearly two decades of CLEAR/J-PAL South Asia’s MEL capability-strengthening experience with NGOs of various sizes in India, as well as with governments, we have found that a 360-degree organisational lifecycle approach is most effective.

When learning takes place across programme design, implementation, evaluation, and scale-up, instead of episodic compliance, adoption is much stronger. Traditional donor-funding structures rarely support these integrated approaches and largely remain short-term with respect to programme components.

MEL capability strengthening requires sustained engagement because the use of evidence is a behavioural and organisational change process, not a one-time technical input or knowledge transfer. Training staff and disseminating tools may provide information, but that does not guarantee evidence-informed decision-making. Our experience shows that the availability of evidence — a dashboard or report, for instance — is often mistakenly equated with the use of such evidence. Sustained capability strengthening allows learners to live through decision cycles with trainers, providing hands-on support as they grapple with real-time trade-offs, incentives

and constraints.

This is not unique to NGOs. Governments face the same organisational challenges, including leadership buy-in, incentives, decision cycles, and competing priorities, making the underlying capability-building constraints fundamentally similar

across stakeholders.

When we draw from our government MEL capability-strengthening portfolio, which has a lot more examples of success for this lifecycle model — because of the availability of early funders — it offers lessons that apply to NGOs as well.

A long-term capability-strengthening model is effective because evidence use depends on behavioural and organisational change, an insight into human behaviour and approaches towards learning that are generalisable4 to NGOs.

This approach has been central to our long-term engagement with the Government of Tamil Nadu (GoTN)5, with whom we have been working since 2012. Our engagements with GoTN over the years, covering MEL diagnostics, training, advisory, impact evaluations, and policy-research dialogues, have helped embed evaluation into its planning and decision-making processes.

Capability emerges through iterative learning-by-doing, when organisations receive support not only to produce evidence, but also to interpret, deliberate on, and apply it at critical junctures. This is something that one-off training or short-term technical assistance cannot achieve.

GoTN is financially investing in our long-term MEL partnership. However, this success required strong donor commitment during the early years from the CLEAR Initiative and the Global Evaluation Initiative, which understood the purpose of investing in government MEL portfolios.

Effective MEL use also requires leadership and an organisational buy-in, not just donor-mandated reporting frameworks. Capability-building efforts falter when MEL is treated as a top-down donor accountability exercise, rather than in the spirit of learning to further improve programme delivery.

As Co-Impact’s Shagun Sabarwal argues6, “Local is best.” Too often, capability-building programmes follow the requirements of the global donors instead of equipping nonprofits to respond to their unique contexts or the needs of

the community.

J-PAL South Asia’s post-training tracer surveys further reinforce this: over 55% of our NGO participants are self-funded, with 47% reporting that financial constraints, limited staff capacity, and lack of leadership buy-in prevent them from applying learning in practice. Without sustained ownership and multiple touchpoints over time, MEL capacity building will remain episodic and fragile, regardless of

training quality.

Supply-side limitations further limit progress. India has organisations such as India Leaders for Social Sector and The/Nudge Institute that provide structured support for fundraising or leadership development. However, hands-on and dedicated long-term MEL support for NGOs remains limited7.

Even short-term MEL providers are limited. J-PAL South Asia has delivered short-term MEL courses to Indian NGOs for close to two decades, including for grassroots organisations reaching upwards of 200,000 participants, yet we see that demand continues to outstrip supply.

Six lessons on building MEL capabilities in NGOs that last:

1. Capacity is not capability: Capacity is evaluation ‘hardware’, providing tools and templates, and training that builds technical capacity, but not the ability for evidence use. MEL capability emerges only when such evaluation ‘hardware’ delivers results, that is, through leadership buy-in, decision-making routines, and organisational norms that underline evidence use.

2. Training individuals is inadequate without an organisational framework: MEL skills cannot be applied in isolation. Donors must invest in organisational systems — dedicated MEL roles, internal learning forums, funding Management Information Systems and data analysis, and integration of evidence into planning and

budgeting cycles.

3. MEL capability building requires behavioural change — and that takes time: As we have learned, workshops rarely lead to organisational change unless supplemented with leadership commitments, follow-ups, accompaniments and multiple touchpoints. Communities of practice and sustained technical advisory matter more than

one-off workshops.

4. Avoid one-size-fits-all MEL frameworks: Lant Pritchett’s principles of ‘problem-driven iterative adaptation’ apply as much to NGOs as to governments (see figure 2). Rigid indicators from donor-mandated frameworks often undermine learning. NGOs need space to adapt MEL systems to local problems and contexts instead of adapting cookie-cutter approaches and best practices that may have worked in a

specific context.

5. Invest in strengthening long-term MEL ecosystems, not just one-off programme activities of organisations in the short run: Sector-wide infrastructure ultimately enables sustainable MEL capability — peer learning platforms, shared curricula, evaluator networks, and partnerships with donors, NGOs and research institutions. Individual grants on discrete project deliverables cannot substitute for ecosystem investment that ultimately enables evidence use by NGOs.

6. When MEL supports the programme lifecycle of NGOs, it enables scale and sustainability: When MEL runs parallel to the programme lifecycle from project conceptualisation or design to programme implementation, evaluation and scale, organisations can test their priors early, adapt during delivery, and leverage evidence in their scale-up journey. Ultimately, MEL enables programmes to scale impact, upholding the effectiveness and long-term sustainability of programmes.

If donors want to invest in programmes that stick, they must move beyond funding MEL as a reporting requirement and enable evidence use. MEL capability building is pivotal in this transition that often gets neglected in funding decisions. This requires long-term engagement with flexible funding and a shift from demanding evidence to building the ecosystem under which evidence can be generated, used and sustained.

1The Role and Contributions of Development NGOs to Development Cooperation: What Do We Know?

By Nicola Banks

2Building Strong, Resilient NGOs in India: Time for New Funding Practices. By the Bridgespan Group

3Why is there a collective silence around capacity building? By Pritha Venkatachalam and Amit Chandra

4The Generalizability Puzzle. By Mary Ann Bates and Rachel Glennerster

5Investing in evaluation capacity development in India: Why it matters now more than ever. By Aparna Krishnan and Shagun Sabarwal

6Local is Best: The next revolution in the history of capacity Building. By Shagun Sabarwal

7What nonprofits need from capacity building programmes. By Manjula Ramakrishnan, Shreya Kedia and Vijaya Balaji