‘Indian minds are multilingual’

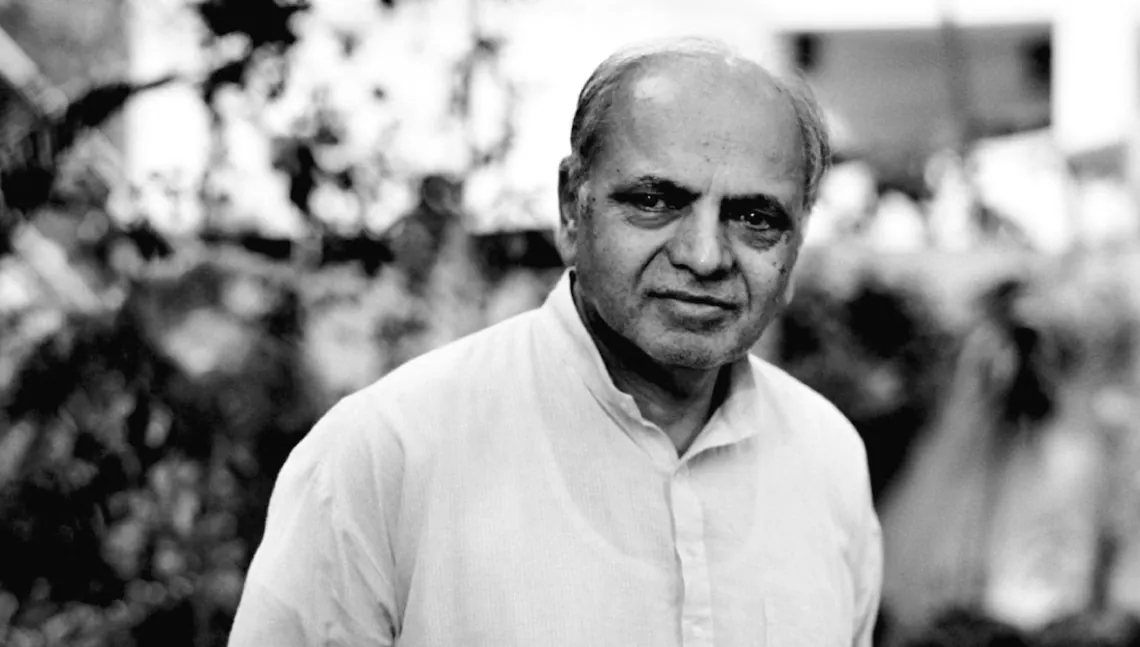

Across a lifetime of remarkable scholarship, Ganesh Narayandas Devy has explored a range of themes and disciplines to better understand “a single subject — India”. This is an unending quest, says the 74-year-old professor, whose extraordinary body of work covers linguistics and languages, literary criticism, cultural studies, anthropology, history, education and philosophy.

Prof Devy wears his learning light as a feather, as he does his multiple accomplishments. He spearheaded the groundbreaking ‘People’s Linguistic Survey of India’, which mapped 780 languages in the country; created the Bhasha Research and Publication Centre and the Adivasi Academy; and is the writer of some 90 books. The standouts in this collection are After Amnesia — his first book in English and winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1993 — Of Many Heroes, A Nomad Called Thief and his latest, India: A Linguistic Civilization.

Prof Devy’s personal story is as compelling as his professional odyssey. Born in Bhor, a village near Pune, his first brush with formal education happened when he walked into the second-standard classroom of a government school near his house. That bizarre beginning — he was allowed to continue after tests and not a little drama — led in time to junior college and his dropping out, overwhelmed by an English-medium education he had never encountered previously.

Then followed a spell in Goa, as a 16-year-old, doing odd jobs and menial labour, using every waking hour reading English classics to get a grasp of the language, making it back into college, completing postgraduation studies, securing a doctorate, and qualifying for a Rotary Foundation fellowship that enabled him to read at the University of Leeds for a second master’s degree.

Prof Devy went on to teach English at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Vadodara. That marked the beginning of a career — and a calling — as a researcher and a writer, and it laid the field for his subsequent expeditions into the realm of knowledge, its structures and its discontents.

A winner of several honours, among them the SAARC Writers’ Foundation Award, the Prince Claus Award and the Linguapax Prize, Prof Devy speaks here to Philip Chacko about his work and his penchant for “describing people, describing life, describing thinking”. Excerpts from the interview:

You have journeyed through a variety of disciplines in your research and your writings. Which of these is closest to your heart?

All of my work is about India. I think of India as a dynamic congregation of many types of people, and I never cease to feel fascinated by the kind of things people keep doing. Ordinary people in ordinary life are great stories. I thought I would try to situate them in various fields of learning. I could not remain a slave to any particular discipline. It is not like I decided this in advance; it just happened.

I moved from literature to criticism to translation to history to philosophy to sociology to anthropology to education, all the while trying to understand one single subject — India. And I think I have understood very little of India; it will take me 10 more lives for that.

How would you characterise the influence of language in the social development of a nation, its people and its culture?

The entire cultural geography of India is based on language. The political economy of India is based on language. Language, therefore, has deeply influenced our being who we are. It is of as much essence to this nation as are bones to a body.

No language is eternal but it is distressing to hear that an estimated 1,500 languages worldwide could disappear by the end of this century. Why is preserving any language a worthwhile endeavour, and why are we failing to do so?

Languages take birth, they grow and they die, but we must remember that they are not biological systems. They are not like animals; they are social systems. And when a language dies, we cannot see proof of it, as you can when an animal dies. When a language dies, it gets assimilated into neighbouring languages. The trace of an old language always enters a new language.

Even a large language can disintegrate — like Latin and Sanskrit did — creating many other languages. This is the natural process and it’s a slow process. Sometimes a word can stay in use for tens of thousands of years. But grammars break down when there is a migration of people into other areas. If economic or political forces compel people to migrate, then their language is in danger of disintegration and disappearance.

When one says languages have to be conserved, one is saying that people need to be supported, livelihoods need to be supported, because a language mobilises people as a community. If that language disappears, the community disintegrates. Therefore, language disappearance is not the vanishing of a single system; it’s doom for an entire community.

Even a large language can disintegrate — like Latin and Sanskrit did — creating many other languages. This is the natural process and it’s a slow process.”

But was this not necessary in the past? The answer is, migration as a phenomenon has entered human life in a big way. At present, 42% of the human population is migrating every day. These people face the risk of losing their languages faster than they would have been lost naturally.

The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 changed the international order. In the years since, the world has become a community of nations. Each nation has to have the ability to defend itself, or it will be gulped up by a neighbouring nation. In such a situation, most nations are trying to be larger than they are. That means imposing a national identity on their citizens and, in the process, restricting regional identities and multilingualism.

The English language did not spread because of colonialism; colonialism spread because of the English language. It’s the same with Russian, French, Spanish and now Hindi, languages spreading to other areas and trying to put neighbouring languages under their shadow. I don’t think that is good for languages or for human communities.

You spearheaded the pioneering People’s Linguistic Survey of India, which mapped some 780 Indian languages. What was the motivation behind that mammoth enterprise, and what did you learn from it?

Much before independence, George Abraham Grierson had carried out a linguistic survey of India. This was the first of its kind in the world, but it was a bit inadequate. A big chunk of the South was left out; secondly, the map of India that Grierson had before him was very different from the map of India after 1947.

In 2007, the Indian government decided to do a fresh survey and this was called the New Linguistic Survey of India. A committee was appointed — I was a member of it — money was set aside and the task was handed to the Central Institute of Indian Languages. For various reasons, from bureaucratic tussles to differences between ministries, the idea fell through.

At that stage, I mobilised my friends from tribal communities and academia. We said that if the government is not doing the survey, we will do it ourselves. Designing the survey was a complex exercise because we have languages of different kinds; every language has different needs and structures.

Grierson had designed his survey in the framework of historical linguistics, with a greater interest in the genealogies of languages. For him the question — which language came out of which linguistic ancestor? — held importance. I set aside history and made geography the backbone of the survey. Grierson had focused on grammar as the heart of language; I decided to focus on the tongue rather than the heart. That’s what people speak as dialects and what people claim as a language.

I said it is not my right to decide whether a given language is a dialect or a language. If people say ours is a language, I should accept their claim because language is a social institution, created by an entire society. For instance, in Kerala there’s the Byari dialect of some Muslim communities. I said, let Byari be a language. Why should I force it into Malayalam, Kannada or Tulu?

“There is a forest of languages growing around us,” you have been quoted as saying. This forest is being denuded, and English and Hindi are deemed culpable to some extent. But is that not how it has always been, languages being created, used and discarded?

A forest has above it a sky that sends rain and strengthens the soil. But that same sky sometimes sends lightning and thunder and trees get uprooted. If their entire education is in English, children will have difficulty writing and reading their own languages. If all administrative communication is in Hindi, then people working in offices will have difficulty writing even English.

What we now notice in India is people who don’t know enough Hindi in reading and writing, and who don’t know enough English in reading and writing. We are becoming a society of people who know many languages but not any one of them well enough. This is a condition of multiple language illiteracy. I am not against Hindi or English; I love both languages. But I also love my Gujarati, my Marathi, my Kannada.

Language has been a contentious subject in India and the issue is on the boil once again. In the context, how do you view the National Education Policy and its three-language formula?

This reminds me of the historical moment in 1952 when state boundaries were to be drawn and language became a big issue. As for now, the language issue has come up precisely when, in the background, there is the looming threat of delimitation. The representation of the people in Parliament is being decided and some fear that their numbers will be reduced and others will benefit. Hence, the language issue as it is surfacing today is not linguistic; it is an issue related to representative democracy.

Edward Said wrote that everyone “lives life in a given language” and that the complication for him — the split — was trying to produce a narrative of his native language, Arabic, in English, the language of his education and writings. What bearing does this kind of split — which is common in India — have on your literary undertakings?

I accepted this split as a natural condition for the Indian consciousness. I always believed that Indian minds are multilingual. I was born in a Gujarati family that lived in Maharashtra and we spoke Gujarati at home. I studied Marathi in school and, later on, I learned some Hindi. Then I learned English. I don’t think of this as a fractured situation; rather, this is an invitation to dream in different spheres.

We are becoming a society of people who know many languages but not any one of them well enough. This is a condition of multiple language illiteracy.”

How many languages do you know?

I have two mother tongues, Gujarati and Marathi; I cannot say one came before the other. I did not study Hindi systematically; I learned it through songs, films and travel. I studied English systematically at the university level, which is why my English is of the books. Sanskrit I studied on my own; it is a language of my quest, and I still have a long way to go. I also know 12 tribal languages.

Different languages spark different kinds of relationships. Actually, even when there is a language I do not understand being spoken around me, I feel as if I belong to that language. I think all languages in the world are a ‘linguasphere’, like there is an atmosphere.

When you look back at your life and all your varied accomplishments, what is it that you find most fulfilling? And what remains unfinished?

That I could remain active, intellectually and socially, makes me happy. My relationship with my wife, Surekha — my life partner for the last 55 years — and my daughter, Rashmi, has given me great strength. Also, all my life I’ve been captivated by music. What gives me energy is not God or nation or religion — it’s music.

I don’t think anything remains, but I’m working on 10 volumes on civilization, covering all nations in the world. Once that is done, I think I would have completed one unit of my quest, describing people, describing life, describing thinking.

Humans have a shared and common future. We have to think together now. We no longer have the luxury of thinking only as a nation, as a culture, as an ethnicity, as a language. That’s the big leap.