- Kalike’s effort has covered 300+ school libraries in Koppal (200+) and Yadgir (100+) districts, with 46,158 children benefitting from them

- Also in the programme are 227 child-friendly libraries in panchayat (village council) areas; these serve 20,000+ readers

- Kalike has supported the setting up of 543 home libraries by children

- Training has been provided to 150 animators, 250 library teachers and 227 panchayat librarians

Seeding the reading

More than 525 school and village libraries in Karnataka have created shared spaces that enable children to bond with books

The morning assembly at the Model Higher Primary School (MHPS) in Ginigera village in Karnataka’s Koppal district is slightly different from that of other schools.

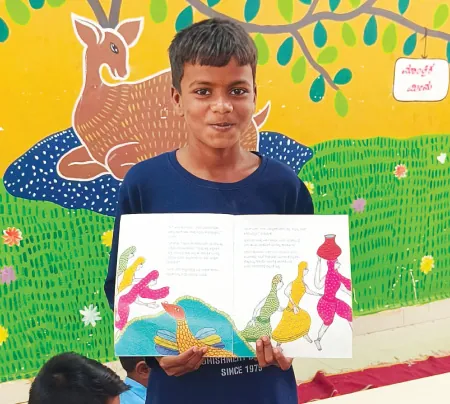

After the national anthem is sung, prayers recited and the message for the day read aloud, 11-year-old Rupa Virupaksha Badigera stands up and introduces her fellow schoolmates to Friend, the Kannada translation of an illustrated book about a naughty cloud named Tultule. This is the ‘book talk’ part of the school’s morning assembly, where a student shares a synopsis of a book of their choice, with just enough information to pique the audience’s interest.

Book talk is one slice of a larger reading initiative introduced in 2015 by Kalike, an associate organisation of the Tata Trusts, under its ‘strengthening school libraries’ programme. The larger objective is to embed the reading habit in children attending the 300-plus government schools in Yadgir and Koppal, two of Karnataka’s lesser developed districts. The library programme is guided by Parag, the Trusts’ initiative that aims to encourage reading.

The programme works to build a lifelong connection between children and books. “We have been involved in strengthening school libraries because we found that most schools lacked dedicated library rooms, age-appropriate books or regular library periods,” explains Shivkumar Yadav, Kalike’s programme officer for education.

Kalike has also helped in the makeover of panchayat (village council) libraries so that children have access to books even when schools are closed.

When Kalike kicked off the library initiative a decade back, the first realisation was that the need was for open doors as much as open minds. “In many schools, books were locked away in almirahs in the headmaster’s room, and most titles were not suitable for children,” says Kalike’s programme director, Girish Harakamani. “We had to start from there.”

Animated effort

Kalike’s efforts went beyond creating library rooms. Its programme team sourced age-appropriate books, engaged with school authorities to assign a library period for every class, and trained teachers as librarians. The intent was to create an enabling environment where students could access age-appropriate storybooks. Importantly, some 40 of the schools involved now have an ‘animator’, appointed by Kalike to conduct reading sessions for students.

“Children are most drawn to storytelling sessions and drawing,” says Aishwarya Gouli, the animator at the Ginigera school. “They interact more, especially among themselves, and they begin to show more interest in reading.” Kalike’s team trains animators like Ms Gouli and equips them with lesson plans to use during their reading sessions. The organisation has trained 150 animators, 250 library teachers and 227 panchayat librarians thus far.

Kalike’s library interventions are for classes IV to VIII and there’s also the newly introduced library corner for younger children. These corners are set up as part of the schools’ foundational literacy and numeracy centres.

The library initiative took a turn when the Covid pandemic struck. That was when Kalike decided to extend the model to panchayat libraries. “We thought that community learning centres would keep children engaged during the lockdown,” says Mr Harakamani. “These libraries were not child-friendly at all, and there were hardly any children accessing them.”

Training tack

To improve panchayat library facilities, Kalike started conducting regular training sessions for the appointed librarians. It also helped bridge gaps in the infrastructure by providing book racks, reading tables, and storybooks.

The training sessions have been particularly effective.

Gavisaiddappa Manglapur has been the panchayat librarian at Ginigera for three decades, but he has had minimal training for the post. “Thanks to Kalike, I have been able to go for training courses and even a three-day field visit to community libraries, including the Mysuru public library,” he says. “This has helped me engage better with children, learn what they like to read, and conduct sessions for them.”

Kalike has turned 227 panchayat libraries in Koppal and Yadgir into child-friendly reading spaces and the difference is visible. Manjula Devi, the panchayat development officer for Ginigera, notes a significant increase in all-round interest. “These are shared spaces and Kalike’s intervention has led to community activities, music, chess and craft,” she says.

Children visiting the panchayat libraries are encouraged to take part in the government’s ‘Take one for mother’ initiative, where they borrow books for their mothers.

To make the library initiative self-sustaining, Kalike has worked on cementing a community buy-in. For each school, a member from the permanent teaching staff is given the additional responsibility of a library-point teacher, who is expected to take on the job of animator. The idea is that a member of the school staff can continue the library sessions even after an animator’s tenure ends.

To build ownership among students, Kalike encourages them to form library clubs. These clubs are tasked with library activities such as book mending, record-keeping and ensuring books are returned on time.

A library on the inside

In 2020, as the Covid pandemic raged and schools went into shutdown mode, a meeting of the Kalike team and the animators it had trained heard about an unusual development — a young girl in a village in Yadgir district had started a reading corner in her home, a space for her and her friends to gather and read.

From the one to the many. There are now more than 540 home libraries in Yadgir and Koppal. These are not fancy by any means: children choose a corner or space in their house, display a set of books — procured on their own or contributed by Kalike — and invite their friends to read and borrow them.

Many of the students are first-generation schoolers, their interest sparked by the concept of home libraries they heard about from their school animators. The children setting up the libraries have found that there are advantages to having their own set of books.

Take 14-year-old Meghana Ramesh Kudrimoti, a student at the Government Higher Primary School in Budgumpa in Koppal district. She wants to be able to access more than one book at a time. Another happy librarian is 13-year-old Suresh Baligar. His father, Pampanna Baligar, sees the home library as a welcome distraction: “Earlier, he would spend a lot of time just loafing around outside. Now he and his friends sit here and read.”

Mapping the impact

With the project spreading and unfolding well, Kalike is planning to conduct a formal impact study. “Though the influence of books and libraries is often difficult to measure, we want to explore how to quantify the impact of this programme on the community,” says Mr Harakamani.

And there is a clear impact. Neelkanth Sali, a 45-year-old agriculturist, says his panchayat library has helped him reconnect with science. Shivkumar HR, headmaster of the Ginigera MHPS believes children often learn morals from the books they read, especially autobiographies.

Mr Yadav from Kalike says he has observed significant changes in children coming through library activity sessions such as reading aloud, book talks and storytelling: improved confidence and social behaviour, creativity and critical thinking skills.

A common upside noted by teachers is an enhanced interest in creative activities. “These children are reading better and paying more attention to their studies,” says Vanashri Kulkarni, library-point teacher at the Government Higher Primary School at Budgumpa in Koppal. “We see an overall development in general, particularly with craft-related work.

Shankarayya TS, the state government’s block education officer for Koppal, is effusive in his appreciation for Kalike’s exertions. “They have changed the libraries into an enabling environment for children,” he says. “Along with animators, they have also created centres that help improve reading and writing habits in children.”

The initiative has had some unintended side effects, a standout being children setting up home libraries (see A library on the inside). “I consider the home libraries as a possible proof of concept,” says Mr Harakamani. “After all, our aim is to turn children into lifelong readers.”

The most remarkable outcome in all of this is that the Kalike library endeavour is spurring a first generation of readers, opening up new vistas for underserved communities.