‘Swachhata is everyone’s business’

Parameswaran Iyer has made a name for himself in the water and sanitation sector in different parts of the world. His most sterling accomplishment, though, has been in his home country, where he heads the gargantuan Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), the largest sanitation initiative ever undertaken globally.

The 56-year-old Mr Iyer retired from the Indian Administrative Service to join the World Bank in Washington and worked with the organisation in Vietnam, China, Egypt and Lebanon. Now, as secretary in the central government’s Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Mr Iyer is at the vanguard of the extraordinary effort to make India open defecation free (ODF). He speaks here to Horizons about SBM and what it represents. Excerpts from the interview:

You have been heading the SBM initiative for two-and-a-half years. What has the experience been like?

The Mission is the world’s largest behaviour change programme and it has been transformed into a massive jan andolan (people’s movement), covering almost the entire country. Being involved with it has been a phenomenal and humbling experience.

This programme has become possible because of our Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s unprecedented move to put sanitation at the forefront of the development agenda. Working with an incredible team in the ministry and with state governments at every level, all the way down to the grassroots, has been a tremendous experience.

Nowhere in the world has a programme like SBM been attempted. What have you and your team learned along the way?

One of the key differences between SBM and the previous sanitation programmes rolled out in India has been the personal championing of the cause by the prime minister. With his backing, the programme was conceptualised on the primary pillars of the ‘community approach to sanitation’. The strategy has focused on the four ‘Ss’:

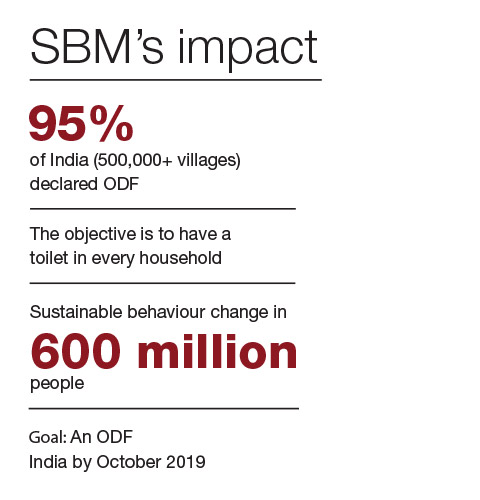

- Scale — to change the behaviour of 600 million people who were used to defecating in the open.

- Speed — with a sunset clause of november 2019 defined in order to build a sense of urgency.

- Stigmas — to change habits and beliefs held for generations.

- Sustainability — to ensure that people do not slip back into their old habits of open defecation.

Will the mission meet its november 2019 deadline to make India free of open defecation? How tough a target is that, even with all the pieces in place?

SBM is well on track to achieve an ODF India before its deadline of november 2019. In parallel, our ministry maintains its focus on sustaining the progress already made on the ground and maintaining the quality of work being done.

The link between access to water and sanitation has been obvious and the government has made policy changes to secure both. What has been the on-ground effect of these changed policies?

A policy decision has been taken under the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) to prioritise the provision of piped water supply (PWS) for ODF villages. In the 500,000-plus such ODF villages, 616,000 habitations have PWS through public stand-posts. The remaining are being covered on priority.

About 80% of all habitations in India are ‘fully covered’, in that they receive at least 40 litres of drinking water per capita every day. About 55% of the rural population has access to PWS and about 17% of households through private connections. Additionally, the central government is now working on a strategy to provide piped water to all households in a fixed time span, well before the ‘sustainable development goals’ timeline of 2030.

The Swajal model being promoted by NRDWP is a demand-driven, community-centred drinking water programme that will be implemented in all ‘aspirational’ districts (those categorised as backward) on priority.

On sanitation and the construction of toilets, the emphasis has shifted from number of units built to behavioural change and sustainability. What sort of difference has this outcomes-over-output approach made?

From the outset, the Mission has been a behaviour change programme, creating demand for safe sanitation and meeting it with the required provisions. What works with such a programme is that even though the output of a demand- or a supply-driven programme is the construction of toilets, in the demand-driven approach the outcome is the sustained habit of using toilets and the adoption of safe sanitation practices.

This has been confirmed by the National Annual Rural Sanitation Survey 2018 — conducted by an independent verification agency under a World Bank support project — which found that 93.4% of households in rural India that have access to a toilet actually use it.

You have been an advocate of the GOBARdhan project, which seeks to generate wealth and energy from waste. What’s the potential here and how important can this become?

SBM (Gramin) comprises two main components for creating clean villages: creating ODF villages and managing solid and liquid waste in villages. With the GOBARdhan scheme, the goal is to positively impact village cleanliness and generate wealth and energy from cattle and organic waste. The scheme also aims to create new rural livelihood opportunities and enhance the incomes of rural people; this plays to an important theme of the overall development agenda. The importance of the scheme is also highlighted in the 3 ‘Es’ it seeks to promote: energy, empowerment and employment.

Having the prime minister as its leading well-wisher and supporter has been a boon to the Mission, but what about the foot soldiers in this people’s movement?

To ensure change at such scale, as is being done by the Mission, one requires leadership from the very top as well as ground-level activation. At the central government level, behaviour change communication is undertaken through mass media campaigns such as darwaza band (or close the door), starring Amitabh Bachchan and Anushka Sharma, which communicate the message of usage of toilets by all.

The SBM foot soldiers — the swachhagrahis — participate in the triggering of behaviour change in the community and in sustaining improved behaviours through inter-personal communication. There are more than 500,000 swachhagrahis across India driving the programme individually through behaviour change interventions at the grassroots.

What’s your opinion of the contribution made by the Tata Trusts and similar organisations to the Swachh Bharat initiative? How vital are such partnerships, and what more can they achieve?

The involvement of the private sector in sanitation is of key importance in not just accelerating the sanitation story of India, but also in sustaining the progress being made.

With swachhata [cleanliness] being ‘everyone’s business’, the private sector is increasingly including mainstream sanitation in their core work. It is stepping up to the plate, an excellent example of which is the work done by the Tata Trusts.

[The Mission acknowledges] the importance of the four ‘Ps’: political leadership, public funding, partnerships and people’s participation.”

Your years at the World Bank took you to Vietnam, China, Egypt and Lebanon. How is the water and sanitation story in these countries relevant to the Indian reality?

The biggest lesson I have learned is that eliminating open defecation is not driven by the construction of toilets; it is driven by changing behaviour at the community level.

The approach must be tailored to specific local conditions. Strong political will and leadership at the highest level, combined with local administrative commitment, are key facilitators in achieving and sustaining success. What is interesting is that SBM addresses all of the above, along with acknowledging the importance of the four ‘Ps’: political leadership, public funding, partnerships and people’s participation.

What kind of memories do you have of your years in the IAS, especially as collector and district magistrate in Uttar Pradesh’s Bijnor district?

My time in the Indian Administrative Service was an important phase of learning for me. As collector and district magistrate in Bijnor, I was faced with various challenges and opportunities in the development agenda, which paved the way for my future career in international development.

It is my experience in the field that fortified my pitch for what we call the ‘PM-CM-DM-VM model’ — the prime minister sets the goals, the chief minister supports it at the state level, the district collector leads at the local level, and village motivators work at the grassroots level.

You represented India as a junior tennis player and you took a break from work to be the coach-manager of your tennis-playing daughter, Tara. What was that experience like?

Taking time to be my daughter’s tennis coach and manager was fantastic. As a former tennis player myself, it was great being a part of my daughter’s journey as she pursued her dream of becoming a professional tennis player. I eventually returned to the water, sanitation and hygiene sector, but the time we spent training and travelling together was definitely a highlight of my life and will always remain a great memory.