Climate action in a time of schizophrenia

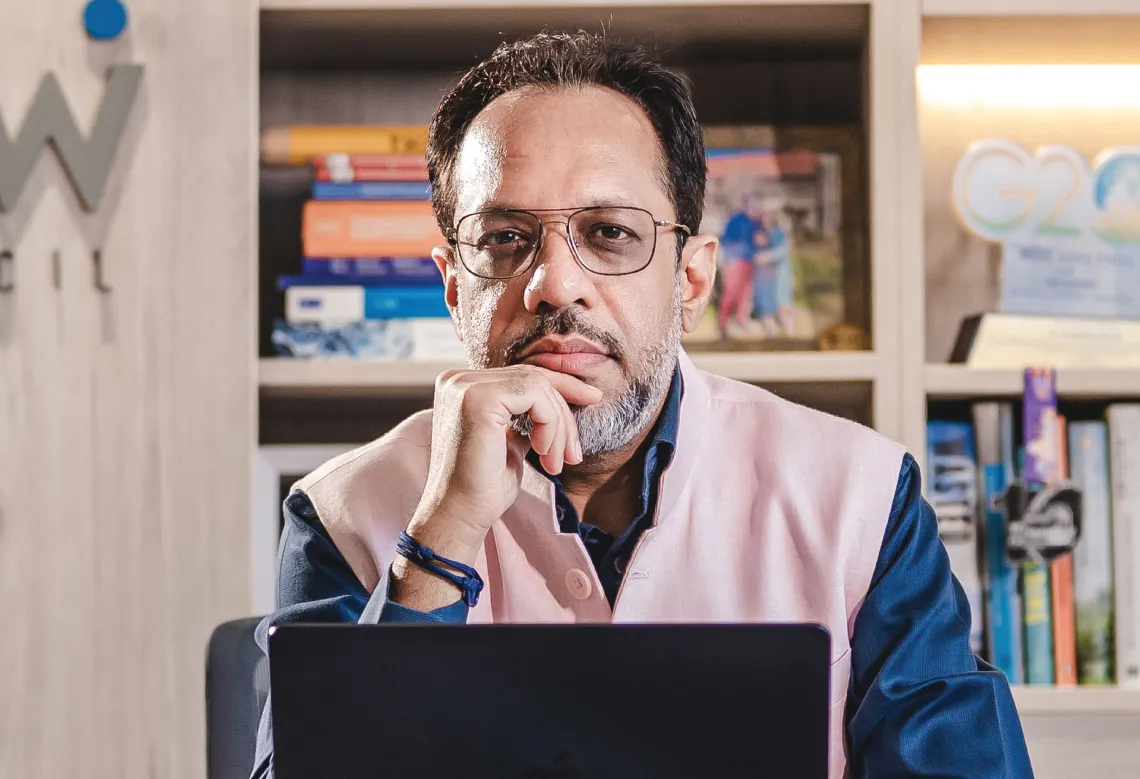

Climate scientist and public policy expert Arunabha Ghosh believes that India’s ambivalence about the steps needed to combat climate change is holding the country back.

The founder and chief executive of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), which ranks among Asia’s leading thinktanks, says policymaking is critical to nudge India towards a desirable direction, but a climate-resilient future starts with a change in our behaviour.

In this interview with Labonita Ghosh, Mr Ghosh explains why the messaging about climate change must be personalised — how it affects our lives, our livelihoods and our neighbourhoods — to grasp the full import of our rapidly deteriorating situation.

Let’s talk about what is uppermost on everyone’s mind in India today: air pollution. How can we tackle it?

The first thing to do is recognise that it will take a few years to get sorted, and only with a mission-oriented approach. We have to understand that air pollution is a challenge not just for Delhi, and not just in the winter months. We have a year-round, country-wide problem of air pollution. This is the biggest public health challenge we face today.

It is also an economic challenge, with close to 3% of our GDP getting impacted, and a human development challenge, because air pollution impacts educational outcomes, brain development, the condition of foetuses and unborn children. We have to think of clean air as an economic asset.

How do we do that? It’s like a patient at a multi-speciality hospital where different teams of specialists target different aspects of a problem. Transport is the biggest source but you also have industry, construction, biomass burning and indoor air pollution. Each of these aspects needs to be addressed.

We must approach climate change in a data-oriented way, where the data is hyperlocal and, therefore, salient for administrators and citizens.”

Have we even made a start with trying to tackle it? The problem appears to be worsening every year.

Targeted work can have an impact. The government and regulators have to keep at it and citizens must also contribute. We Indians are schizophrenic. We are economic agents by day and citizens by night. Citizens want clean air but economic agents — the same human beings — do not want to drive a cleaner vehicle or pay a higher cost for waste disposal. As long as this schizophrenia persists, no amount of public programming can work, and that’s why we must treat it collectively.

Do we need a similar mission-oriented approach to mitigate the climate crisis in India?

We already have a mission-oriented approach there. The National Action Plan on Climate Change was launched in 2008, and under that, various missions were launched as well. The most successful has been the solar mission, which started in 2010. At that time India generated less than 20 megawatts of solar energy; today it produces more than 100,000 megawatts.

We have become the world’s fourth-largest clean energy power in terms of deployed capacity. Another reasonably successful effort is the National Mission for Energy Efficiency. All this is good, but the climate crisis is worsening. When we talk about climate risks, we say that the probability of something bad, or really bad, happening goes up over time.

We must approach climate change in a data-oriented way, where the data is hyperlocal and, therefore, salient for administrators and citizens. If I told you India is in a bad shape, what would you do with that information? Individual citizens focus on what it means for their lives, for their livelihoods, for their neighbourhoods.

About 80% of our population lives in areas that are highly vulnerable to extreme hydrometeorological disasters and 55% of our subdistricts have seen a decrease in [rainfall from] the southwest monsoon over the last decade. The point is, climate change is now about climate variability.

Heat stress is going to affect our economic growth while we are still building our country. Bridges, buildings and railroads are under construction and there’s a lot of employment out there. But if the ‘hot days’ in India’s districts increase by an additional four to twenty each summer, that would translate into tens of millions of man-days lost because it’s too hot to work in the open. And not least, we are at our most vulnerable when it comes to water, whether it’s with rainfall or declining water tables.

There appears to be an absence of public consciousness in India about climate change. How do we change that?

I don’t want to suggest that there’s an easy answer, but the first thing we must do is make our analyses more salient. If a bunch of nerds are doing some modelling and saying we’re going to get impacted, ordinary citizens may not care. But you can make it salient by saying, for instance, that if you are a construction company, your construction activities will slow down by 20% because of heat stress. Whether it is from a human-centric or a capital investment perspective, or even from a livestock perspective, you have to make the information salient to those who may care about it.

Second, we have to embed this in broader economic ministries, not just the environment ministry, because we all care about economic growth and poverty reduction. Only then will you get a pro-economic perspective of how this will impact things. A third approach is a more positive one. Many startups are going to be looking at advanced technology — consumer tech, AI, fintech, etc — and sometimes these are all linked. AI and its modelling capabilities can help us create better predictive analytics with regard to climate.

Once we internalise this, we will be able to grasp our bottom-up sense of vulnerability and our top-down sense of macroeconomic challenges, as well as our opportunities in terms of using technology as a new driver of growth, as a new vector of innovation and startup energy. Then we may begin to change the way we approach the idea of climate resilience.

How can public policymaking contribute to climate action?

The role of public policy is absolutely central; it must be the initial spark that lights the fire. Let me give a philosophical or normative reason for this. The primary responsibility of the state is to protect its people. The right to life is at the heart of what the state has to deliver; everything else follows from there.

Climate change impacts our lives. At a normative level, internalising that climate change is not just the next heavy rainfall or the two hot days you have to endure, but a chronic crisis that impacts your life and livelihood. That makes public policy a driver of climate action. Now, at an instrumental level, how do you do it? First, we must recognise what is driving climate change. The energy system we currently have is the biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions. We must use public policy to fix that energy system, globally and nationally.

The public policies that we have had in terms of launching a solar mission or setting targets for clean energy are ways in which new technologies and innovations are enabled to flourish. It’s equally important that public policy be consistent and long-term, because fluctuations and oscillations create investment uncertainties.

The second point is that public policy needs to go beyond the energy sector and start embedding the standards of action needed from other economic sectors. Public policy has to set benchmarks. For example, SEBI has instituted regulations that require the largest 1,000 companies to report on how they are becoming more climate-oriented. This is not just about the energy sector or clean transport; it signals that all economic sectors matter.

A lot of the problems that we face today with climate change, not just in India but across the world, stem from our preoccupation with production emissions. For example, the emissions from a factory that makes certain things. But why is that factory making those things? Because we, as citizens, demand it. Why are we not asking our individual behaviours to shift so that the factory can make electric rather than diesel vehicles, so that the cotton your T-shirt is made from is sustainably sourced? This will not come from a bleeding-heart approach. It sometimes takes public policy interventions to nudge behaviour.

What is India’s approach to energy transition? And our objectives?

India, as well as other developing countries, is going through not one, but four energy transitions. Number one is getting energy in the first place. When the [United Nations’] Sustainable Development Goals were announced in 2015, India had the largest number of people anywhere in the world without access to electricity. In response, the government created two schemes by which, in just 18 months, 30 million homes got access to electricity for the first time.

Second, we are going to see a lot of migration from rural to urban areas, which means that energy demands and energy patterns will shift from rural to urban. This requires more energy efficiency in our buildings, factories, transport systems, even in our home appliances. The third factor is making sure our energy becomes cleaner and cleaner.

The fourth transition is our deeper integration into global energy markets. That means not just securing oil and gas like in the past, but securing what we call the fuels of the future: minerals, solar panels, batteries, wind turbines and the like. There is a fifth transition as well: pairing energy transition with the digital revolution. Digital distribution helps us decentralise energy systems and make our homes, appliances and cars talk to one another.

We have been brainwashed; we have to ask our children to open their minds and imagine that a new and different world is possible.”

Can we imagine a future without fossil fuels? What are your hopes and misgivings about this?

I believe we don’t have an option [but to move away from fossil fuels]. I’m not suggesting that energy systems will change that soon. Today, an electricity transformer is exactly what it looked like in the late 19th century. Energy systems are like sloths; they take very long to shift course. Our hopes and misgivings have to be recalibrated accordingly.

The fear is of two kinds. First, the interests of those currently in power may try to slow things down. The transition must happen in an orderly manner or there will be a backlash. You have got to manage this transition not just technologically or financially, but also politically.

My second fear relates to a lack of imagination. We are all sort of in the matrix, but we’ve got to imagine a future where we live differently, eat differently, move and interact differently. We have been brainwashed; we have to ask our children to open their minds and imagine that a new and different world is possible.