Securing the flow

Innovative technology and natural conditions have been employed to provide clean water to rural regions in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana

For more than a decade, Laxipuram village in the Anakapalli district of Andhra Pradesh didn’t have proper sanitation. Wastewater from kitchens and sewage would flow into the streets, dragging along all kinds of trash, and drains would get clogged with sludge. Some of this wastewater would also run into nearby water bodies and fields, polluting them. A foul odour hung over the village and, worse, it became prime breeding ground for mosquitoes and vector-borne diseases.

“This was a problem all through the year,” says Ganapathi Naidu, a member of the Laxmipuram gram panchayat (village council) and a third-generation farmer. “Sewage and plastic waste would flood agricultural plots and damage crops. After we lost almost 80 acres of cultivable land to the menace, many villagers decided to give up farming and work as labourers in nearby areas. We also had to live with constant illnesses; typhoid, malaria and chikungunya were common.” It was small relief, adds the 43-year-old Mr Naidu, that the water table and drinking water sources did not get contaminated.

The problem was, strangely enough, compounded by the implementation in 2020 of the central government’s Jal Jeevan Mission, which aims to provide piped water to every rural Indian home. With more houses among the 950-odd in Laxmipuram getting improved access to potable water, more wastewater began to be generated, without any significant solutions for its disposal.

It’s the same story that plays out in thousands of villages across India with poor civic amenities. What sets Laxmipuram apart is the turnaround it has pulled off. This is now a ‘lighthouse village’ — a model of a clean, green and healthy habitation with much that others in the district can learn from.

The path to a cleaner life for Laxipuram’s residents began getting paved in 2022, when the Tata Trusts and their partner organisation, the Vijayvahini Charitable Foundation (VCF), launched a ‘greywater treatment programme’ in the village. (Greywater refers to water discharged from kitchens and bathrooms that doesn’t contain faecal matter or urine.)

Tech to the rescue

A ‘compact acarine mite utilising system’ (CAMUS), a low-energy, high-quality wastewater rejuvenation technology, has been used to treat and clean almost 25 kilolitres per day of household greywater and make it reusable. The CAMUS setup has reduced stagnation, enhanced village cleanliness and strengthened water security. The treated water is now used for farming, gardening and civil construction, which was earlier managed with water delivered by tankers.

“This technology mimics nature,” says Manoj Kumar, team lead, water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) and energy with VCF, about the treatment process. “It follows the same principles as some plant species that create moisture during photosynthesis. CAMUS contains different components that clean the wastewater as it passes through them. Also, the technology is low maintenance and requires cleaning and top-up only once in two-three years.”

When VCF approached the sarpanch (village head) of Laxmipuram, he was keen to employ the technology. He provided a plot for the biotech unit and used government-allotted funds to make drains that would channel household wastewater directly to it.

After operating it for a year, VCF has now handed over the plant to the gram panchayat. “We have one channel of clear water that goes directly into the paddy fields and have managed to reclaim most of the 80 acres we had lost to contamination,” adds Mr Naidu. “Many villagers are now returning to agriculture because we have enough clean water for irrigation.”

With the integration of household toilets, waste management systems and behaviour change demonstrated by members, the Laxmipuram community has shown the way for other villages to follow. In Annaraopeta — another lighthouse village — in the NTR district of Andhra Pradesh, VCF conducted a clutch of awareness activities on greywater.

“Water security entails three aspects: water for domestic use, for irrigation and for the environment,” says Mr Kumar. VCF has lent a hand here through WaSH initiatives in Andhra Pradesh.

Since December 2024, it has been working with communities in Pullacheruvu and Yerragondapalem villages in the Prakasam district to build structures for better water management and irrigation.

In Chintapalle and Rajavommangi villages in the Alluri Sitharama Raju district, VCF is starting work on diversion-based irrigation systems, a cost-effective method that uses gravity to channel water from nearby streams and rivers to agricultural fields.

Expanding on the options for safe drinking water, VCF has deployed ‘inline chlorination’ systems in 200 villages in its project area, enabling 20,000-plus rural households to access potable drinking water through tap connections. This low-cost, scalable technology effectively reduces microbial contamination and ensures safe drinking water at the distribution point for rural families.

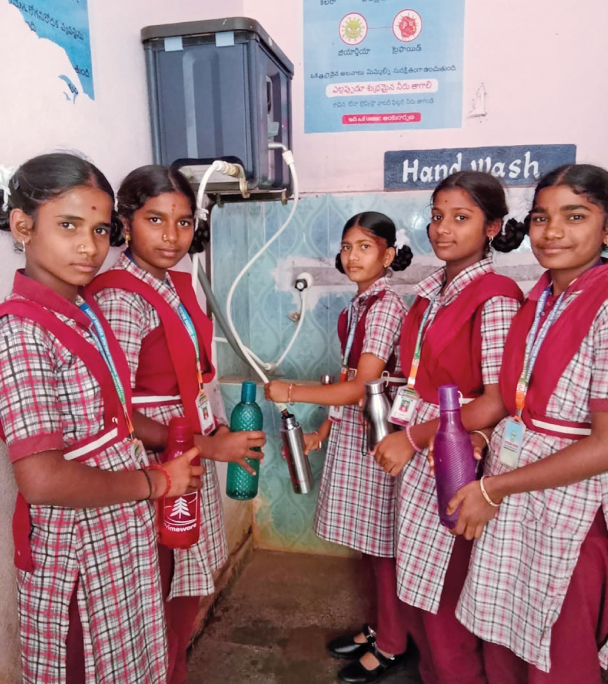

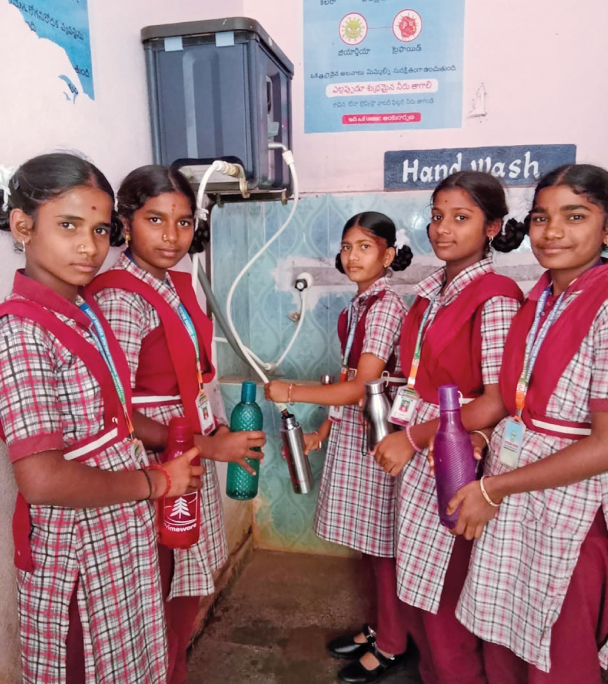

In 2024, in the neighbouring state of Telangana, the Tata Trusts and VCF embarked on a programme to provide safe drinking water to 50 schools in the Shadnagar area in Ranga Reddy district. Co-funded by UNIBIC Foods, this initiative aims to provide hygiene education as well for the staff, improving not only the school environment but also the health, attendance, and overall well-being of students.

This is particularly important for a residential school like KGBV Kondurg in Pulusumamidi village, which houses about 430 students from classes 6 to 12. “We receive Mission Bhagiratha water at our school,” says Nissy Shakeena, an official with the school. This refers to a vast network of pipes supplying water to all of Telangana from the Krishna and Godavari rivers and their reservoirs.

Unsafe at school

“But there are often leaks in the pipes and the water gets contaminated,” adds Ms Shakeena. “The water we received was turbid, with bacteria and even faecal matter in it. Students who drank this — and earlier there was not much of an option — would fall ill. Absenteeism was high.”

Then the school started purchasing bottled water. With a daily requirement of more than 200 litres, the school had to spend about ₹30,000 a month on this. Following complaints, local authorities promised to install three water-filtration systems in the school, but they never arrived.

With funds from UNIBIC Foods, VCF organised for water-purification systems with certified filters. These were then installed in each of the 50 school buildings in Shadnagar and placed at an elevation to enable gravity assistance to push the water.

“VCF’s trainers have explained to us how to operate the system and the older students take turns to clean the filters,” says Ms Shakeena. “They’ve also taught us how to test the water periodically. Having safe drinking water in our school 24/7 has made a lot of difference to our students and their health.”